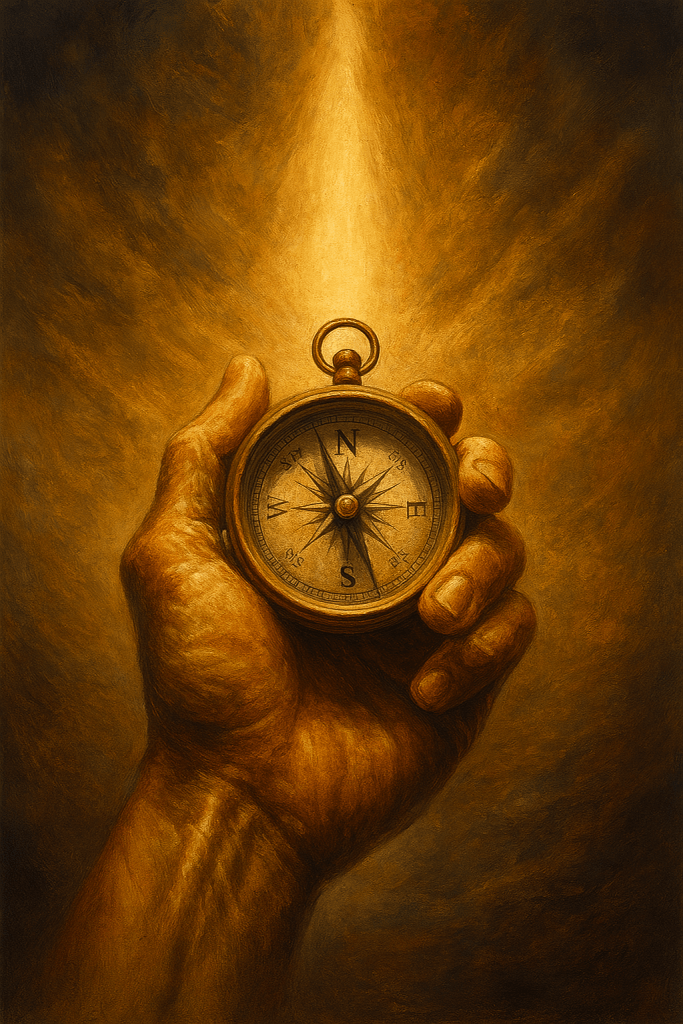

People, as a general rule, don’t choose their beliefs

They give their core conviction to a single, ultimate Being

Or Philosophy

Or Cause

And then their beliefs are given to them by that source

So, choose your core conviction wisely

People, as a general rule, don’t choose their beliefs

They give their core conviction to a single, ultimate Being

Or Philosophy

Or Cause

And then their beliefs are given to them by that source

So, choose your core conviction wisely

I spoke a little bit yesterday about how some are more loyal to a group than to God. They let society be the highest authority of what is right and what is wrong, or of what can be believed and what is preposterous. I’d like to delve a little deeper on this matter, examining the reasons for this “popularity ideology,” and how it gives people reason to stop believing in God.

A major contributing factor to this is that people tend to optimize their learning by relying heavily on their trust in an authority. We do not all look through telescopes or microscopes to discover what can be found there, we just accept what we have been told by those that have.

And this predisposition to trust isn’t a flaw in us, either. It is an essential characteristic for us to progress as a race. Taking things on authority allows us to “stand on the shoulders of giants,” depending on the discoveries that came before us to be valid so that we can build something greater on top of them. Research and discovery is conducted at the outer limits of the human understanding, pushing the boundaries further than they’ve ever been pushed before. Were it otherwise, and each of us had to individually reinvent the wheel, our progress would be limited to only the things that can be accomplished in a single life-time.

While building on past work without a full context can result in catastrophic errors, and occasionally has done so, the net result has clearly been positive. We move forward and improve more often than we stumble and fall backward.

But what is the point of all this? Simply that we should recognize that we have this built-in instinct to believe anything claimed by another person, so long as they seem rational and decent. We hear what they say, and we try to update our model of the world with that new information so that we can save the time it would take for us to verify it on our own. As already discussed, this is a good thing in many cases, but clearly it also creates the potential for us to be manipulated from time-to-time.

If a seemingly-rational person teaches a principle that does not perfectly align with the beliefs that we held before, we tend to stretch and rotate our convictions to make the new one fit also. If we cannot make the old fit with the new, because the two are in direct contradiction, we will find ourselves divided, which is both logically and emotionally painful. Sooner or later, one conviction will give way to the other, if only to restore our inner equilibrium.

All too often, the decision of which side to align oneself with has less to do with the strength of the arguments, and more to do with social pressure. It is far easier to turn one’s back on a passive object, like the Bible, than the people who are actively arguing against proper theology. It is easier because the Bible’s arguments can be shut out by just refusing to read its passages, whereas the messages of society crowd in on us no matter what we do. We feel much more obligated to give some sort of response to the challenge of other people than to faceless books. Thus, just to restore a sense of logical consistency, we might very well discard the old faith, abandon the texts it comes from, and replace it with the philosophy espoused by the incessant babbling.

So what is Reason #3 for Disbelief? Allowing our convictions to be overrun by our instinct to adopt the views and opinions of other people. This mostly represents the rational side of social pressure, but obviously there is an emotional side to it also. Tomorrow we will examine that.

I have discussed how we tend to be shaped by our cultures, how when most people move from one place to another, they will gradually morph from the beliefs of their old community to the beliefs of their new one. I have discussed how this occurs slowly, by osmosis, gradually constraining our perceptions and imaginations until we cannot conceive of other alternatives, and the only sensible way of living seems to be the one that we currently follow.

Of course, one does not have to move to change their perceptions. The places that we live are themselves of a transient nature. Through years and generations, new philosophies arise in the same place, and what once felt like home now feels strange and unfamiliar. Here again, most people will adapt to the new norm, which is a problem if the new norm is perverse or built on lies. Without even knowing it, the general populace will gradually defile themselves, inhaling the polluted social air until it fills them.

This brings to mind a saying from Jesus: “Not that which goeth into the mouth defileth a man; but that which cometh out of the mouth, this defileth a man” (Matthew 15:11). In this I read that it is inevitable for us to be surrounded by the corrupt philosophies of the world. We are going to consume bad thoughts and bad ideas in our daily life, and that’s unavoidable. But that does not have to mean that we, ourselves, must also be corrupted. Where we should be concerned is when we start to hear those false perspectives coming back out of our own mouths. Then we know that we have not only consumed, but have also been converted.

I have seen people who tend to be more resistant to this change, who hold to their convictions, even though it makes them unusual in their changing society. It is rare to keep oneself anchored when corruption permeates us as a way of life, but it is possible. At least, it is possible when one is intentional about holding to what is true. If one is idle and inattentive, they might hold out a little longer than others, but I do believe they will lose their grip eventually. Being properly anchored to what is true is something that we must practice actively.

Yesterday I mentioned that most people are only socially converted to their beliefs. They gradually, through osmosis, adopt the faith, the principles, and the paradigms that their society repeats to them. Perhaps even more importantly, they adopt the limitations that come with society’s beliefs.

When we hear a falsehood repeated enough times, it goes from sounding strange and offensive to familiar and comfortable. And when our mind becomes aligned with any principle, true or false, it establishes boundaries to reject any competing notions.

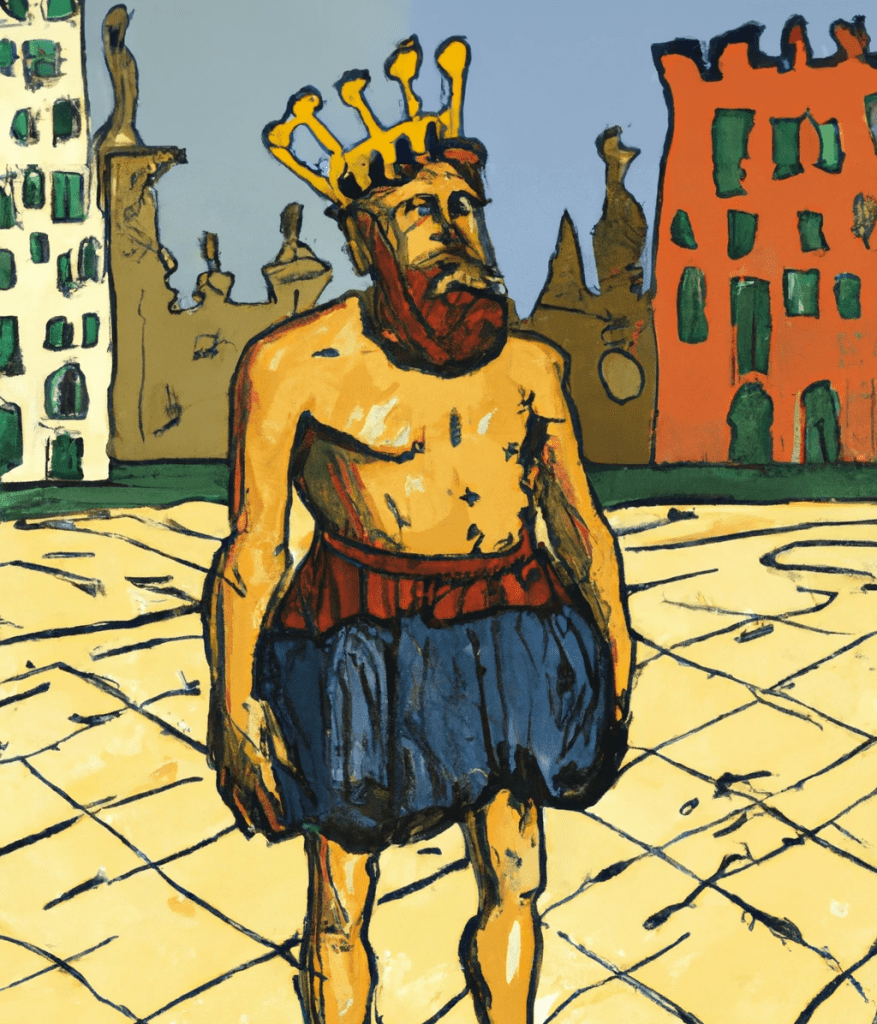

One of the great allegories for our day is the story of The Emperor’s New Clothes. It’s widely recognized as a lesson on peer pressure and vanity, but there is another important detail in it that we must not miss: the people are duped into participating in the grand lie because they have boundaries set on their minds to keep them from seeing that it is a lie.

Remember, the yarn that is spun by the swindling tailors is that the fabric can be seen only by those who are worthy. After the first servants and counselors confirm that they do see the clothing, bounds start to be laid on everyone else’s thinking. Everyone just assumes that if they cannot see what the others do, then it must be because they are unworthy. They have had blinders put on them by the social pressure of others’ claims, such that they cannot even consider the possibility that everyone else is lying. The notion doesn’t even cross their minds.

This lie by the tailors is particularly effective because it preys upon the insecurities of the villagers. “Impostor syndrome” is a common sensation that falls upon us all. None of us are so clever or so good as we would like to be, nor so much as most of us pretend to be. Everyone feels a fraud inside, and so not seeing the Emperor’s clothes, and by extension being told that they were unworthy, only confirmed what the villagers had already suspected about themselves and they didn’t even try looking for other options.

This is why it is a young boy, still innocent and with no self doubts, who is finally be able to see through the charade. The idea that he would be unworthy was the notion that could not cross his mind, and so he was able to rightly see the truth of the matter. And when he did, it was not only the king who had his nakedness exposed. Every villager now knew that his neighbor was full of self-doubt and shame, and would absolutely lie to hide it.

I am going to pause my analysis of Exodus for eight posts, so that I may cover a topic that's been weighing on my mind recently. Today I will begin my discussion on what we ought to align ourselves to in life, and the dangers that follow when we are misaligned.

***

There are a considerable number of Christians who become distressed and divided between the commandments of God and the principles they have been taught by society. Once these two sets of voices were nearly enough aligned that one could blend them with only moderate twisting of the self. Today, they are more firmly at odds to one other, creating an impossible divide, and a person feels they must choose one or the other.

Given the choice between the commandments of God and the principles of the world, many end up hearkening to the world, but do so under the assumption that they are listening to their own inner voice. This is a defining characteristic of our world today: that everyone must be “true to themselves,” choosing “what they know in their heart to be right.” And while there is a wisdom to this thinking in theory, one has to acknowledge that most of the convictions that come out of us did not actually originate from within our hearts at all.

We are highly social creatures, and we gain our perspectives and beliefs from our surroundings, subtly and invisibly, by osmosis. We might be surrounded by voices that stress principles we do not originally agree with, but over time, without recognizing why or how, we will start to hear the same arguments coming out from inside of us. We are convinced and converted without ever realizing it.

I saw this firsthand when I was a missionary in the West Indies. I visited many countries and districts. Some were primarily Christian, some primarily Hindu, and some primarily Muslim. A common phrase in each area was “born an X, die an X,” where X was the predominant religion in that region.

But the saying wasn’t true. I know this because when I transferred to other areas, I would find people who had moved there from the same place that I had left, and usually they had given up their old religion to adopt the new one that surrounded them. And this went in every direction. Hindus to Christians, Christians to Muslims, Muslims to Hindus, etc. The locals that never moved were firmly convinced that they could never change their beliefs, but the evidence suggests that their stalwartness was most often due to their environment more than their personal convictions.

And this doesn’t just have to do with religion. Travel to different places and you will see that attitudes coalesce from the community towards science, education, politics, justice, lifestyle choices, and every other domain that people have opinions on. Spend long enough in these places and you might find yourself starting to think the same way, too.

The fact that one can move to a different environment and change their beliefs does not condemn the original value system, nor elevate the new one, it merely shows that most people are socially converted only. Yet they say to themselves, “I’m just listening to my own heart.” In truth, what they are listening to is what their heart has been constrained to believe by their culture.

But Daniel purposed in his heart that he would not defile himself with the portion of the king’s meat, nor with the wine which he drank: therefore he requested of the prince of the eunuchs that he might not defile himself.

Now God had brought Daniel into favour and tender love with the prince of the eunuchs.

And the prince of the eunuchs said unto Daniel, I fear my lord the king, who hath appointed your meat and your drink: for why should he see your faces worse liking than the children which are of your sort? then shall ye make me endanger my head to the king.

COMMENTARY

Now God had brought Daniel into favour and tender love with the prince of the eunuchs

Yesterday I spoke of how Daniel’s moral beliefs were at odds with the prince of the eunuchs’ fears. The two men were at an impasse, but notice from this verse that the relationship between them was not hostile. Daniel had already established a positive relationship with those whom he wished to have respect his culture. Read again the prince’s rejection and you will see that it is not motivated by malice, only by a fear of self-destruction.

In fact all of the exchanges in this story seem to be laced with a certain tenderness, both from Daniel and from his caretakers. All that follows in the tale is only able to occur because it is founded on the love between Daniel and these men.

Surely this is a lesson to all of us when discussing differences in our beliefs. These matters will go far more smoothly if we are able to first establish a mutual respect between us. And if we want respect for our different beliefs, first we need to establish a respect for one another’s person. Love for one another is the foundation of equality.

We come to God to be refashioned by Him. He promises us “A new heart also will I give you, and a new spirit will I put within you” (Ezekiel 36:26). I think most of us have a pretty basic expectation of how this refashioning is going to go. He’s going to take away our craving for sin, make our hearts kinder, and give us a deeper appreciation for the sacred. And at first, this might be exactly how things proceed.

At some point, though, there usually come changes that are unexpected. You see, each of us is an imperfect mortal, and invariably have misconceptions about God. At some point He is going to try and correct those, to show us who He is more truly. Beautiful as these moments are, they can also be disconcerting. We can have strong, emotional ties to our misconceptions, and letting go of them can feel like heresy.

Even more troubling, sometimes people struggle to let go of their misconceptions of God without letting go of Him entirely. They recognize a legitimate flaw in their previous belief system, but let go of the belief instead of the flaw.

With this study I would like to explore how we can safely navigate doubt, questions, and evolving perspectives. Have you experienced any of these in your life? Did you ever find it difficult to separate misguided periphery from the actual core of the gospel? In what ways did your spiritual life change after being enlightened?