The Need for Miracles)

In the last post we discussed so-called moral dilemmas present us with only bad choices, each a compromise of conscience, but if we are willing and creative enough to find it, there is typically another option that sidesteps the dilemma and allows us to keep on the straight and narrow. First, we have to move outside of the manufactured box that our tester has put us in, then see the full range of possible choices, and finally be willing to accept the consequences for sticking to what is right.

Indeed, a common theme all throughout the Bible is people who are faced with exactly these sorts of situations, who then have to step outside the bounds of their initial perception and rely on a miracle to accomplish good and retain their souls. Think of Lot, who saw his only choices as letting the wicked men of the city either rape his guests or his daughters, but who was then saved by angels. Think of Joseph who could either put Mary away in secret or have her stoned for adultery, but who then received a heavenly message to show him that she truly bore the son of God. Think of Solomon who had two women claiming to be the mother of the same child, with nothing in their testimony to show him whom to believe, but who was blessed with wisdom to find out the truth.

Moral dilemmas, and their outside-the-box solutions, are a key theme in the scriptures. When the righteous are faced with no-win scenarios, that’s when the hand of God becomes manifest to show them another way. Indeed, the entire point of the gospel is that it provides a surprise solution to a damned situation. Many of us will sin and earn the suffering of hell, while those that die in their innocence are still swallowed in the grave. No matter which path we take through this life, we’re damned, at least we were until a Savior presented us a miraculous alternative.

The Master of Third Options)

It comes as no surprise that Jesus, himself, was a master of resolving seeming no-win, moral dilemmas. I think more than any other figure in the Bible he was put to the test with contrived situations that tried to get him to compromise himself one way or another.

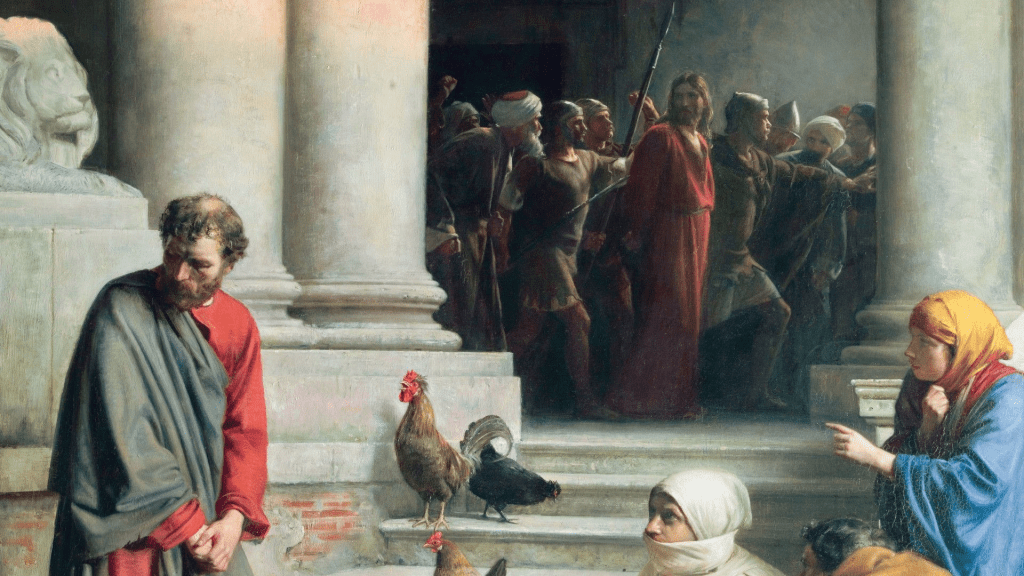

Think of when the Pharisees brought him the woman taken in adultery, and asked if he would uphold Moses’s law, which required the stoning of the woman. Would he deny the law? That would be heretical. Would he condemn her to death? That would go against his mission to forgive and to save. Jesus stepped outside of their trap, though, and said, “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.” In so doing, he touched their guilt and got them to slink away in shame.

But it’s not as though he was denying the justice of the law. Jesus was still worthy to stone her, but also, he was able to forgive her because he would take her stoning upon himself when he laid his life down as a ransom for the world. Thus, Jesus did not transgress justice, nor embrace condemnation. He found a third way to satisfy justice and make space for mercy.

Think also of when he was asked whether the people should pay taxes to their oppressor Caesar. On the one hand, he could say that yes, they were required to pay their taxes, which would offend the people. Or he could say no, that they should defy Caesar, which would make him an enemy of the state. Jesus, however, chose a third option. He showed the people that their entire framing was wrong. They were putting too much value in worldly currency, thinking that it amounted to anything of moral weight in the eyes of the Lord. He reminded them that worldly treasure and spiritual sacrifice were two separate things, one properly pertaining to the world and one to God. By helping to disentangle the two, and setting the spiritual as superior to the temporal, Jesus found a third path that both approved the paying of taxes while also diminishing its importance in the broader scheme of things.

The stories of Jesus and others in the Bible shows us that we may be given traps where it appears that there are no good solutions, but that if we have some ingenuity, or even some divine intervention, the moral way is still there for us. As Paul told the Corinthians, “With the temptation,” God will “also make a way to escape” (1 Corinthians 10:13).